The title of this post may seem surprising to some. Why should the late, great, Guy Bourdin need redeeming? It feels like of late, it's become very, very unfashionable to talk about Bourdin in terms of his (whisper it) misogyny. Even The Guardian, in their recent potted biography of Guy(www.guardian.co.uk/artanddesign/2011/mar/21/guy-bourdin-when-sky-fell), was quick to play up his genius and play down his woman-hating, portraying him as an eccentric artiste, and the odd ways he directed his female models as endearing little quirks. Perhaps this has something to do with his death - it's difficult to speak ill of the dead, especially when they're so talented, or maybe because of the recent film about him, When the Sky Fell Down: The Myth of Guy Bourdin. Bourdin is so very chic at the moment. And it's difficult to level serious charges at the chic, for they can always shrug off their work as satire or parody or a challenge to the viewer. Biographies of Bourdin make for unsettling reading. He was a man who lived Freud writ large: who went for red-haired women that reminded him of his mother, whose first wife killed herself and whose suicide he went on to re-stage in fashion shoots. The way he treated the models was notably horrible: 'On one occasion Bourdin wanted to cover the pale bodies of two models in tiny black pearls. He had his assistants cover the models in glue and attach the pearls. The layer of glue interfered with the skin's ability to regulate temperature and exchange oxygen; both models passed out. As his assistants hurried to remove the pearls and the glue, Bourdin is reported to have said "Oh, it would be beautiful to photograph them dead in bed."' (www.utata.org/salon/37437.php Sunday Salon). But it never seems quite fair to assess an artist via their life, rather than their work, so, by all means, type "Guy Bourdin" and "models" into google, and read on at your leisure. Because, it's really the work itself, isn't it, which is so objectionable. Quite possibly because it's so seductive - the bright colours, the glossy surfaces that coax you into these photographs, that wear down your shock at just how pretty these images of violence are.

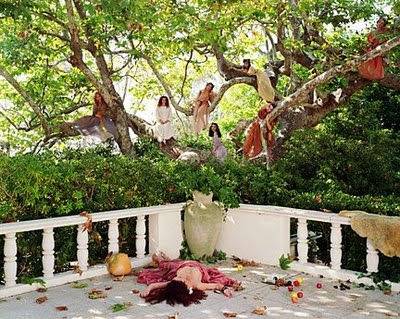

From Edgar Allen Poe to Alfred Hitchcock to David Lynch, one image endures. Why are dead/wounded/vulnerable women always, always in style? Comparisons are always drawn between Bourdin and Helmut Newton. But these comparisons don't seem very fair. The argument goes, both ph otographers introduce sordid reality into the world of fashion. But the comparison doesn't really follow. As you can see from the photo on the left, while Newton's images are heavily sexual and often sadomasochistic, the similarities stop at the eyes of the women. Newton's women either gaze off disdainfully into the middle distance, as if too bored by the viewer to give them the time of day, or stare back unflinchingly. These images are sexual, but the power lies with the women - they've got a sort of tigress like quality. In Bourdin's work, when you can see the eyes, mostly they're averted, not disdainfully, but submissively, geisha-like. It seems interesting that more often that not in Bourdin's work you can't see the eyes of the models because their heads have been cut out of the shot, or they've been trussed up in harnesses or contorted painfully so all you can see are pert bottoms or stockinged legs (though Newton, admittedly, likes a good stockinged leg shot, himself) or swan necks as a red-haired belle dies gently, prettily in a bathtub.

otographers introduce sordid reality into the world of fashion. But the comparison doesn't really follow. As you can see from the photo on the left, while Newton's images are heavily sexual and often sadomasochistic, the similarities stop at the eyes of the women. Newton's women either gaze off disdainfully into the middle distance, as if too bored by the viewer to give them the time of day, or stare back unflinchingly. These images are sexual, but the power lies with the women - they've got a sort of tigress like quality. In Bourdin's work, when you can see the eyes, mostly they're averted, not disdainfully, but submissively, geisha-like. It seems interesting that more often that not in Bourdin's work you can't see the eyes of the models because their heads have been cut out of the shot, or they've been trussed up in harnesses or contorted painfully so all you can see are pert bottoms or stockinged legs (though Newton, admittedly, likes a good stockinged leg shot, himself) or swan necks as a red-haired belle dies gently, prettily in a bathtub.

otographers introduce sordid reality into the world of fashion. But the comparison doesn't really follow. As you can see from the photo on the left, while Newton's images are heavily sexual and often sadomasochistic, the similarities stop at the eyes of the women. Newton's women either gaze off disdainfully into the middle distance, as if too bored by the viewer to give them the time of day, or stare back unflinchingly. These images are sexual, but the power lies with the women - they've got a sort of tigress like quality. In Bourdin's work, when you can see the eyes, mostly they're averted, not disdainfully, but submissively, geisha-like. It seems interesting that more often that not in Bourdin's work you can't see the eyes of the models because their heads have been cut out of the shot, or they've been trussed up in harnesses or contorted painfully so all you can see are pert bottoms or stockinged legs (though Newton, admittedly, likes a good stockinged leg shot, himself) or swan necks as a red-haired belle dies gently, prettily in a bathtub.

otographers introduce sordid reality into the world of fashion. But the comparison doesn't really follow. As you can see from the photo on the left, while Newton's images are heavily sexual and often sadomasochistic, the similarities stop at the eyes of the women. Newton's women either gaze off disdainfully into the middle distance, as if too bored by the viewer to give them the time of day, or stare back unflinchingly. These images are sexual, but the power lies with the women - they've got a sort of tigress like quality. In Bourdin's work, when you can see the eyes, mostly they're averted, not disdainfully, but submissively, geisha-like. It seems interesting that more often that not in Bourdin's work you can't see the eyes of the models because their heads have been cut out of the shot, or they've been trussed up in harnesses or contorted painfully so all you can see are pert bottoms or stockinged legs (though Newton, admittedly, likes a good stockinged leg shot, himself) or swan necks as a red-haired belle dies gently, prettily in a bathtub.I suppose the question is, can we enjoy Bourdin's work? For me, the problem of Bourdin is the problem you have when you crack open a Bukowski novel, or the latest Bret Easton Ellis. How far do they have to push you before you finally concede, shutting the book, leaving the gallery, the way they act towards women makes me queasy? Especially with Bret Easton Ellis, it's started to feel that what was once one disturbing element amongst many (gang violence, numbness, consumerism) has become the element of a Bret Easton Ellis novel, the star attraction. His books are now marketed accordingly (see, if you have a strong stomach, http://www.thedevilinyou.com/). T he worst of Bourdin is his legacy in the fashion industry. Legions of fashion photographers have dumbed-down his work, featuring less of his brilliance and more of the sex. Obviously, there was the controversial Opium ad, with Sophie Dahl, as pale and copper-haired as any of Bourdin's women, naked and nubile and drugged in high heels. But more mundanely, the hundreds of American Apparel ads of women bent over, particularly the one which caused so much uproar when on a billboard in Times Square - I can't find an image for it online, but it was a girl bending over in nothing but tights, something which seems the mirror image (minus the great use of colour)of a Bourdin photo. You can't help but wish that Helmut Newton, as revered and respected as he is in the art world, had had a more enduring effect on mainstream fashion photography. A legion of strong, amazonian, voluptuous women, even if they were in stirrups, would feel like a breath of fresh air after all these photos of broken, vulnerable women.

he worst of Bourdin is his legacy in the fashion industry. Legions of fashion photographers have dumbed-down his work, featuring less of his brilliance and more of the sex. Obviously, there was the controversial Opium ad, with Sophie Dahl, as pale and copper-haired as any of Bourdin's women, naked and nubile and drugged in high heels. But more mundanely, the hundreds of American Apparel ads of women bent over, particularly the one which caused so much uproar when on a billboard in Times Square - I can't find an image for it online, but it was a girl bending over in nothing but tights, something which seems the mirror image (minus the great use of colour)of a Bourdin photo. You can't help but wish that Helmut Newton, as revered and respected as he is in the art world, had had a more enduring effect on mainstream fashion photography. A legion of strong, amazonian, voluptuous women, even if they were in stirrups, would feel like a breath of fresh air after all these photos of broken, vulnerable women.

he worst of Bourdin is his legacy in the fashion industry. Legions of fashion photographers have dumbed-down his work, featuring less of his brilliance and more of the sex. Obviously, there was the controversial Opium ad, with Sophie Dahl, as pale and copper-haired as any of Bourdin's women, naked and nubile and drugged in high heels. But more mundanely, the hundreds of American Apparel ads of women bent over, particularly the one which caused so much uproar when on a billboard in Times Square - I can't find an image for it online, but it was a girl bending over in nothing but tights, something which seems the mirror image (minus the great use of colour)of a Bourdin photo. You can't help but wish that Helmut Newton, as revered and respected as he is in the art world, had had a more enduring effect on mainstream fashion photography. A legion of strong, amazonian, voluptuous women, even if they were in stirrups, would feel like a breath of fresh air after all these photos of broken, vulnerable women.

he worst of Bourdin is his legacy in the fashion industry. Legions of fashion photographers have dumbed-down his work, featuring less of his brilliance and more of the sex. Obviously, there was the controversial Opium ad, with Sophie Dahl, as pale and copper-haired as any of Bourdin's women, naked and nubile and drugged in high heels. But more mundanely, the hundreds of American Apparel ads of women bent over, particularly the one which caused so much uproar when on a billboard in Times Square - I can't find an image for it online, but it was a girl bending over in nothing but tights, something which seems the mirror image (minus the great use of colour)of a Bourdin photo. You can't help but wish that Helmut Newton, as revered and respected as he is in the art world, had had a more enduring effect on mainstream fashion photography. A legion of strong, amazonian, voluptuous women, even if they were in stirrups, would feel like a breath of fresh air after all these photos of broken, vulnerable women.